Although many people in Israel and the United States have been focused on political elections, I am still reflecting on the interfaith coalition that was forged during the ten day study mission to Israel and Palestine, Sharing Perspectives/ Path of Abraham, which I co-led for the fourth time. As an introduction to our program, Rev. Dr. Karen Hamilton of Toronto, Imam Ibrahim Mogra of Britain and I shared thoughts about the idea of pilgrimage in Jewish, Christian and Muslim traditions. This is what I taught about pilgrimage and Zionism.

My teacher, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, wrote that he could never be lost because he knows that he is a descendent of Abraham and that he is going to the days of the Messiah. In the Torah tradition, pilgrimage is not simply movement, it is going in a direction, a vector toward Jerusalem, toward a promised messianic moment.

In Hebrew, pilgrimage (oleh regel) is “to ascend on foot” during the three pilgrimage festivals: Passover, Shavuot and Sukkot. The Hebrew word for pilgrimage is hag, similar to the Arabic hajj, based on the root word which means “circle”. A pilgrimage is a journey where we go out and circle back, returning from it transformed.

Where do Jews go? “To the place the Eternal your God will choose as a dwelling for his Name” (Deut 12.5). Where is that place? The same location to which God directed Avram: “to the land of Moriah… to the place God had told him… And Avram called the name of that place …on the mountain of the Eternal it shall be seen” Genesis 22). Another tradition also links this place with Eden, "A river went out of Eden to water the garden, and then it parted and became four tributaries” (Gen 2:11).

The Temple Mount in Jerusalem is understood by Jewish tradition to be Mount Moriah, the place where Adam and Eve were buried, "ground zero”, the place that links heaven and earth, where the order of the universe is maintained through ritual and rite. We, too, ascended there.

For Jews, the entire Land of Israel is also a destination of pilgrimage and promise. Just as Abraham went up to that place, so was Moses instructed to lead the people of Israel up to the Land: “Go up to the land I promised Abraham, Isaac and Jacob” (Exodus 33:1). Even though he was not permitted to enter the Land of Promise, Moses told the people: "Behold, I have set the land before you: go in and possess the land which the Eternal swore unto your ancestors, to Abraham, to Isaac and to Jacob, to give unto them and to their seed after them.” (Deuteronomy 1:8).

Even in Exile, the people of Israel looked to return to this Land. The canonical Christian order of the Hebrew Scriptures ends with the prophet Malachi speaking for God, saying “Behold, I shall send you Elijah the prophet before the coming of the great and awesome day of the Eternal” (Malachi 4:5). But the Jewish Bible ends with Cyrus’s decree: “The Eternal, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and he has appointed me to build a Temple for him at Jerusalem in Judah. Those among you of all God's people—may the Eternal God be with him—have him go up (va’ya’al)". (2 Chronicles 36:23). The stem of the final word, “va’ya’al”—have him go up—is the same root as the noun for immigration to Israel: Aliyah.

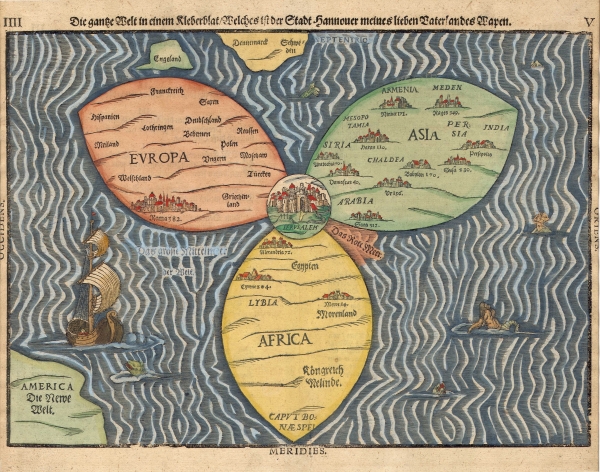

Pilgrimage is seen by the Bible as extending beyond the Jewish people. The prophet Isaiah anticipates a universal ascent. “And it shall come to pass in the end of days, that the mountain of the house of the Eternal shall be established as the top of the mountains, exalted above the hills, and all nations shall flow unto it” (Isaiah 2:2). The religious valence of the Land Israel was so significant that one famous map, published by the German Protestant theologian, Heinrich Bünting in his book Itinerarium Sacrae Scripturae (Travel through Holy Scripture, 1581), places it at the centre of the known world.

Today, the map is found within the Eran Laor maps collection in the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. A mosaic model of the map is installed on the fence of Safra Square at the site of Jerusalem's city hall.

The Jewish yearning of the Land was expressed through prayers to God for a hoped for return to the Land and an orientation in prayer toward Jerusalem. The great Spanish medieval poet Yehuda ha-Levi, wrote, "My heart is in the east, and I in the uttermost west. How can I enjoy food… while Zion lies beneath the fetter of Edom (Christianity), and I in Arab chains (in Muslim Spain)?” Rabbi Moses ben Nahman (Ramban, 1194-1270) believed that settlement in the Land was a commandment and that the commandments were to be observed in exile only in preparation for the return to the Land.

Rudolph Otto identifies two responses to the Holy: "Mysterium tremendum et fascinans" (fearful and fascinated mystery). He argued that humans are drawn to the sacred and in awe of it. For some Jews, despite desire for the Land, there also was dread. Rabbi Meir of Rothenberg (13th c, Germany) warned against going to the Land because sinning there was worse than violation of the commandments in the Diaspora-Exile. The allure of the Land was met by fear of not living up to the high holiness demanded of the place.

In the 19th century, most rabbis opposed the early Zionists, because those young Jews rejected traditional Judaism in favour of a socialist revolution against religious belief and behaviour. Other rabbis eventually supported political Zionism and saw the return to the Land as part of the "first flowering" of messianic redemption.

The ideal of pilgrimage for contemporary Jews includes the sacred sites that were inaccessible to Jews from 1948-1967, as well as the natural beauty of the Land and the exciting technological developments, cultural opportunities and culinary delights of the State of Israel. Currently, some Jews (of various political stripes) remain adamantly secular and others take settlement of the historic areas mentioned in the Bible to be a spiritual imperative. Most traditional Jews, however, maintain a deep attachment to Jerusalem and the Land of Israel with a recognition that security considerations and religious compromise lie in the future.

The great Hasidic teacher, Rabbi Nahman of Bratzlav, taught, “Wherever I go, I’m going to Jerusalem.” For the vast majority of Jews, Jerusalem and Israel remain at the centre of our religious yearning. I encourage you to give consideration to your feelings about the Land of Israel, how they are similar to, or different from, your engagement with the State of Israel, which may also differ from your attitude toward the Government of Israel. We carry a complicated spiritual, emotional and political legacy about this land, state and government which means so much to our people.